Community groups work to mitigate Iraq’s water disaster

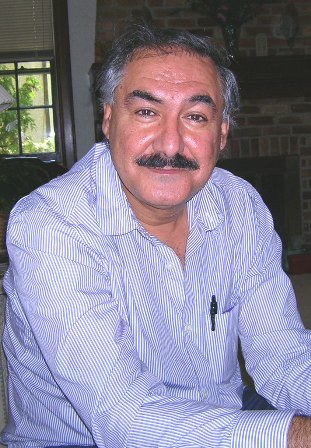

University of Kufa Professors Askouri and Al-Radhi describe Iraq's water crisis at University of Minnesota workshop. Photo: Kathlyn Stone

University of Kufa Professors Askouri and Al-Radhi describe Iraq's water crisis at University of Minnesota workshop. Photo: Kathlyn Stone

Preoccupied with sanctions and occupation but not reconstruction, the U.S. leaves water crisis it created in Iraq to individuals and NGOs to solve.

Twenty-three schools in Najaf, Iraq’s 10th largest city, now have clean drinking water, something they lacked a year or two ago.

That leaves 850 schools to go, said Samera Al-Halawi, a member of the Najaf Chamber of Commerce. Al-Halawi and 13 other Iraqi civic and educational leaders have been in Minnesota since Sept. 18 as part of a delegation wishing to advance a “Water for Peace” project and celebrate a new Najaf-Minneapolis Sister City agreement.

Samera Al-Halawi, a member of the Najaf Chamber of Commerce and Water for Peace delegation. Photo: Kathlyn Stone

By the time the group departs on Saturday, its members will have met with hundreds of educators, community leaders and activists, and other individuals who have pledged to keep working to alleviate the suffering caused by a lack of clean, healthy water.

Many events have conspired to destroy Iraq’s water supply, explained physics professor Dr. Najm Askouri of the University of Kufa in Najaf. Askouri and other members of the delegation shared a discussion with environmental and biology educators and staff at the University of Minnesota- St. Paul Campus Wednesday.

The water infrastructure supplied by the British in the 1970s is substandard and crumbling, said Askouri. Economic sanctions throughout the 1990s ended with the U.S. invasion but were followed by years of bombings and military occupation. Chemicals, such as chlorine needed to kill E.coli, amoebiasis and other bacteria that travel throughout the untreated water supply and seep into ground water, are in short supply. Scrap metals from deserted tanks and other weaponry containing radioactive uranium are routinely salvaged and recycled into pipes and other tools for transporting water. The Euphrates and Tigris Rivers – the waters that gave birth to Mesopotamia – have been diverted out of Iraq into the neighboring countries of Turkey, Iran and Syria. Climate change has also dealt a blow in Iraq. Water supplies have declined and experts fear the remaining marshlands will soon become deserts. Projects initiated by the United States and other countries have repeatedly been sidelined by corrupt U.S. contractors and Iraq ministries.

Grassroots leaders fill a void

Najaf is located about 100 miles (160 km) south of Baghdad, and just west of the Euphrates River.

It is also the hometown of Sami Rasouli, an Iraqi-American who had made his home in Minneapolis for 30 years before returning to help his people after the U.S.-led invasion in 2003. Rasouli, with support from human rights activists from Minnesota and around the country, initiated numerous community efforts, all of which continue to grow including the Muslim Peacekeeper Teams, which lent crucial aid to the people of Fallujah following the massive bombing campaign just days after the 2004 U.S. presidential election. He launched the Iraqi Art Project, which has the dual purpose of promoting peace and understanding through art, and generating income for Iraqi artists whose works are put on display in the United States, and Letters for Peace which attempts to tear down barriers of misunderstanding through the exchange of letters between American and Iraqi children.

Sami Rasouli. Photo: Kathlyn Stone

The most ambitious project to date, the Water for Peace program, is a collaboration of Muslim Peacemaker Teams and the Iraqi & American Reconciliation Project, headquartered in Minneapolis.

Water for Peace is one of a handful of citizen-led projects scrambling with few financial resources to mitigate the growing water crisis in Iraq. Project organizers work with an Iraqi supplier who sells three models of water purifications systems ranging in cost from $250 to $1,000 that purify from 189 to 1,500 liters of water per day. The smallest filtration system can supply clean water for a school with about 100 students; the largest can supply a 200-bed hospital with adequate clean water. Each system depends on a small electrical generator that costs $250. Electricity, too, is in short supply.

Samera Al-Halawi, the Najaf Chamber of Commerce member, oversees the Water for Peace installations.

“We live on top of a lot of wealth [the oil fields],” Al-Halawi said through an interpreter when speaking to a group of women human rights activists Wednesday evening. “But we live under the poverty line. After these meetings we hope you will put the pressure on your government. Our country is destroyed.”

Water for Peace also collaborates with the national Veterans for Peace (VFP) organization which began working on water facility reconstruction projects in Iraq in 1999.

VFP initially sent delegations to Iraq to help repair water infrastructure systems but stopped following growing violence and animosity toward the United States, according to Art Dorland, chair of the VFP’s Iraq Water Project.

Dorland, a Vietnam veteran living in Cleveland, Ohio, who made two visits to Iraq in 1999 and 2000, said he’s “chomping at the bit” to go back to Iraq and help. He calls the water project “My personal reparation for the people of Iraq for what my government has done to them.”

Over the last few years the veterans have been working with local engineers who install the portable water purification units in schools, hospitals, refugee camps, mosques and other public facilities, Dorland said. VFP has raised about $50,000 toward the purchase and installation of Sterilight water purification systems in Iraq over the last two years, he said.

Some of VFP’s most remote installations took place in Misan province, home of the Ma’dān, the so-called “Marsh Arabs” who live in the Tigris river basin. The Ma’dān live a lifestyle that has changed very little since the ancient Sumerian times, some 5,000 years ago. Their buildings are constructed of bundled reeds and closely resemble images found in early Mesopotamia artwork. The Ma’dān were nearly destroyed when Saddam Hussein drained much of the swamplands in the 1990s.

Water purification system installed in a meeting house used by Ma’dān, or Marsh Arabs, in Misan province, southern Iraq. Their bundled reed architecture is some of the oldest in the world, pictured on Sumerian artworks prior to 3000 BC. Photo: Veterans for Peace

VFP sent filtration systems to be installed in a meeting hall used by village men, and at a Misan school and a clinic.

Progress on a micro scale is still progress, and it’s inspiring.

Now to the macro level. Stuart W. Bowen, Jr., Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction, reported in March of this year that the planned reconstruction of Iraq’s infrastructure was a bitter and wanton failure of oversight and of leadership -- a failure that cost the American people tens of billions of dollars and the Iraqi people years of hardship.

Bowen’s most recent report warns that the government has failed to make needed changes and that the experience of Iraq is being repeated in Afghanistan. (See the report “Hard Lessons: The Iraq Reconstruction Experience, February 12, 2009,” and testimony before the Committee on Armed Services, “Effective Counterinsurgency: How the Use and Misuse of Reconstruction Funding Affects the War Effort in Iraq and Afghanistan, Office of the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction, March 25, 2009)

Officials could learn from these individuals and service organizations who aren't waiting for the government to act, but on their own are filling a void, one filtration unit at a time.

Related:

Iraq's health care system crippled by staff and medical supply shortages

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg

I would like to make an observation however, concerning the US role in reconstruction. It is only fair to say that the US put an awful lot of money into reconstruction at the beginning, but several major problems were encountered.

a) Local corruption which siphoned off many millions of dollars.

b) The systematic sabotage by insurgents of electrical, water and other amenity reconstruction, including oil pipelines which supply Iraq with much-needed revenue.

c) The killing by insurgents of many local people who had 'collaborated' with 'the enemy' made local reconstruction personnel hard to find. (Not to mention the killing of Westerners.)

d) The price of guarding installations was estimated to be a debilitating drain on reconstruction resources.

In other words, and to be fair, although there certainly was a reluctance by US hawks to invest in reconstruction, the efforts begun were not uniquely undermined by the US but by insurgent action too, as well as Iraqi government corruption.

Post your comment